One of the great mysteries of the world — less decipherable to some than quantum theory, chatty dentists or the “poke” option on Facebook — is first-time starters.

For those who are equally befuddled by the plot twists on “Keeping Up with the Kardashians”, first-time starters are horses that have never raced before and they are often hard to assess because there is little in the way of cold, hard data — or even hot, pliable data — to work with.

Sure, one can analyze the breeding or consult a pedigree expert (approximately one in every three racing fans on the internet) and, of course, there is no lack of trainer data to look at, but the only concrete numbers available are workouts — and that’s where it gets tricky.

As I learned when I posted the results of an earlier study I did on Facebook, everybody seems to have an opinion about what workouts mean and how to evaluate them.

Some people believe there is absolutely no way to objectively measure the effectiveness of equine exercise. I beg to differ. Physically speaking, horses and humans are actually quite similar. For example, a human skeleton averages 206 bones, while a horse’s skeleton averages 205. Horse’s lungs are also comparable to our own, with a large left and right lobe and a smaller accessory lobe on the right side.

What’s more, an international team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University discovered a lot of similarities between the DNA of horses and humans, including numerous chromosomes that were virtually identical. Heck, Time Magazine even claimed that horses and humans share many of the same facial expressions. Quoting a study from PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed scientific journal, Time pointed out that humans possess 27 Facial Action Coding Systems (FACS), while horses have 17 — more than dogs (16) or chimpanzees (13).

Given this, it seems to me that we might be able to find some things — both positive and negative — to look for in workouts that might aid us in our assessment of first-time starters.

So, to start with, I consulted my database of more than 50,000 races run at tracks across the fruited plain and Canada since 2012 and obtained the following statistics on first-time starters in both claiming and non-claiming events. However, rather than listing winning percentages and impact values as is the norm, I zeroed in on the thing that actually matters — net return. This tells us how profitable — or not — a particular factor is.

Claiming Races

- ALL first-time starters.

Number: 9,876

$2 Net Return: $1.47

Non-Claiming Races

- ALL first-time starters.

Number: 18,309

$2 Net Return: $1.45

As you can see, these digits are worse than what one would expect from betting horses randomly ($1.48 net return for a $2 win wager) — but only mildly so. It’s also interesting (at least to me) that the numbers are so similar for claiming and non-claiming events. (All the handicapping books say that first-timers in claiming races are virtual throw-outs.)

The next thing I looked at was how old the horse’s last workout was. Here is what I found:

Claiming Races

- Last workout within the past week (7 days).

Number: 4,535

$2 Net Return: $1.58

- Last workout more than a week (7 days) old.

Number: 5,341

$2 Net Return: $1.37

Non-Claiming Races

- Last workout within the past week (7 days).

Number: 8,935

$2 Net Return: $1.50

- Last workout more than a week (7 days) old.

Number: 9,374

$2 Net Return: $1.41

Well, on this count, those old handicapping tomes come up aces, as I always read that, in claiming races especially, recent and consistent works are paramount. And this appears to be true in non-claiming affairs as well, although the effect of a recent work is not as pronounced it would seem.

Next, I looked at the distance of the last work — something that I believed from experience would be telling.

Turns out, I was right.

Claiming Races

- Last workout less than four furlongs.

Number: 2,527

$2 Net Return: $1.16

- Last workout 4-5 ½ furlongs.

Number: 7,036

$2 Net Return: $1.54

- Last workout six furlongs or greater.

Number: 313

$2 Net Return: $2.29

Non-Claiming Races

- Last workout less than four furlongs.

Number: 5,427

$2 Net Return: $1.32

- Last workout 4-5 ½ furlongs.

Number: 12,335

$2 Net Return: $1.49

- Last workout six furlongs or greater.

Number: 547

$2 Net Return: $1.81

In claiming races, final workouts of less than four furlongs in distance produced a loss of nearly 42 cents on every wagered dollar; in non-claiming races, the loss was 34 cents per dollar bet. But look at the data on final workouts of six furlongs or greater: Here, we see a profit of almost 15 cents in claiming affairs and a loss of less than a dime in non-claiming events.

Lastly, I looked at the most controversial workout factor of all — time.

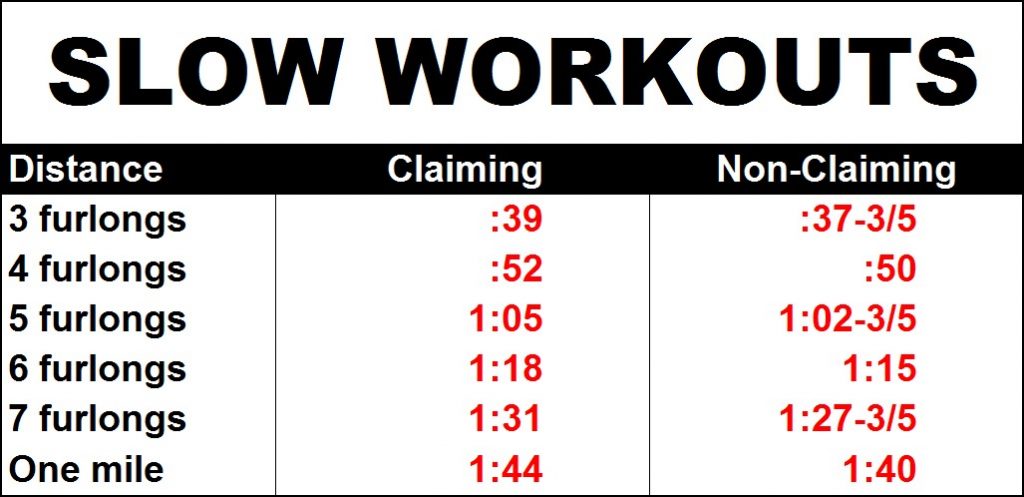

Because what constitutes a “fast” work is open to interpretation and often dependent on effort (not to mention the definition of “handily” and “breezing”), I decided to view time as a potential elimination factor. Hence, I looked for horses whose last work qualified as “slow” per the chart below:

Claiming Races

- Slow last workout.

Number: 1,496

$2 Net Return: $0.89

Non-Claiming Races

- Slow last workout.

Number: 7,113

$2 Net Return: $1.19

Once again, the numbers are astounding. Contrary to popular opinion and regardless of individual training styles, it seems clear that a slow last workout does about as much for a horse as a treadmill set at “1” does for humans — absolutely nothing.

So with all this in mind, I combined the factors I’d tested above to see if I could define a decent workout, one that might make first-time starters a little more palatable from a betting standpoint:

Claiming Races

Last workout:

- At least 6 furlongs.

- Seven days old or less.

- Not slow (see chart above).

Number: 101

$2 Net Return: $3.73

Non-Claiming Races

Last workout:

- At least 6 furlongs.

- Seven days old or less.

- Not slow (see chart above).

Number: 113

$2 Net Return: $2.41

Pretty amazing. Three simple rules produce spectacular profits with first-time starters in both claiming and non-claiming races. Now, before you tell your boss to “shove it” and start betting on firsters for a living, keep in mind that my original database consisted of approximately 50,000 races… and it generated a total of 214 plays.

That’s not exactly going to pay the rent.

Still, the results are encouraging. At the very least they demonstrate that one can apply broad standards to workouts and needn’t rely on Internet gurus or a friend of a friend of the trainer to assess the merits of a horse making its career debut.